13 September 2019

We would like to acknowledge that this walk takes place on and with Noongar Country, in what is also now known as Perth, Western Australia, and with Derbarl Yerrigan, in what is also now known as the Swan River.

Walking-with Derbarl Yerrigan entails walking-with a permanently polluted world. This blog post is not taking a moral stand about achieving a perfectly clean and pristine river system, but rather grapples-with how we might we might incite new forms of ‘’response-ability” in a permanently polluted world (Liboiron, Tironi, Calvillo, 2018).

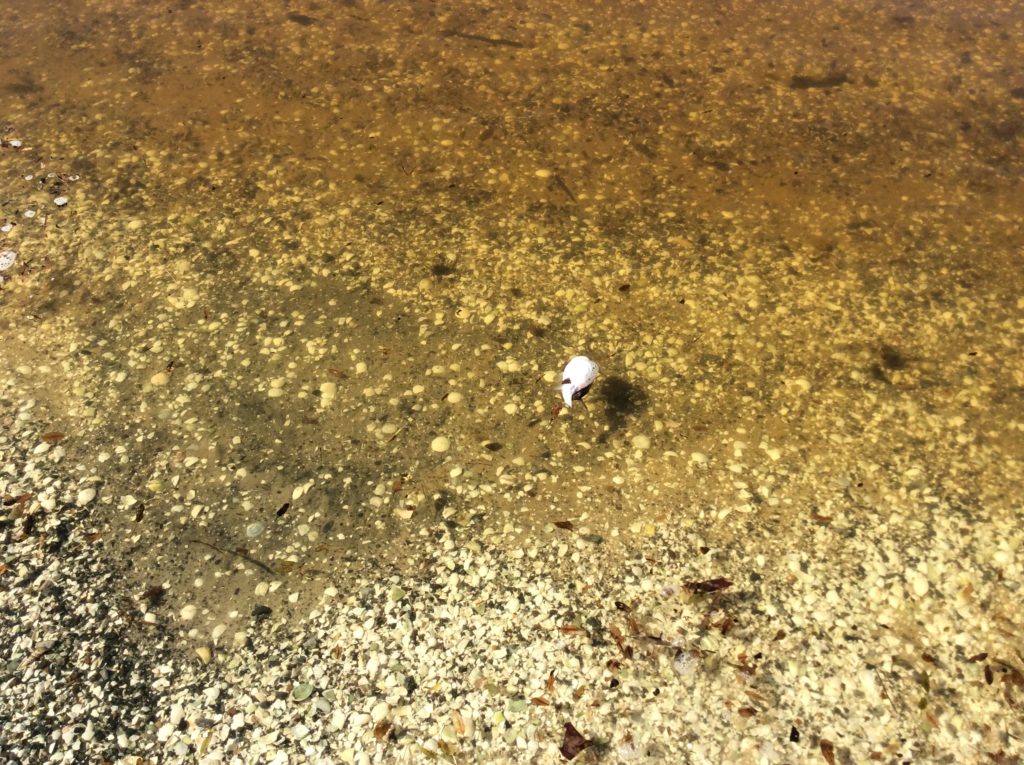

Sunshine, clear blue skies, warm and still air describes the day for this walk. No rough waves today. Sitting on the concrete ledge, with feet dangling, we notice the calmness of Derbarl Yerrigan. Gentle and slow water movements meant we could see the bottom of the river.

“Shells”

“Look, fish.”

“A lot of fish today”

“There are tadpoles”

“More fish” (pointing at the school of small fish swimming. Darting one way, and then another).

Then one of the girls asks, while pointing out towards Derbarl Yerrigan, “What’s that white line?”

“Maybe that’s bird poo” she says.

Walking towards the sandy beach, still on the concrete ledge, we can clearly see the lines of white-brown foamy stuff. We’ve seen this foamy stuff before. It is what was carrying/catching/moving all those feathers a few weeks ago. Looking a second, third, and fourth time we notice that this foamy stuff is gathering at the concrete ledge. Foamy white stuff grows.

One fish, two fish, three fish, all dead fish. That’s how many we see bloated, swept up, but still part of Derbarl Yerrigan, on the foreshore. Finally, a child notices. We haven’t seen dead blowfish (often called ‘Blowies’) here before. This is new. These are common blowfish, also known as banded toadfish and weeping toado, and most people find this fish to be a nuisance because they eat bait. Blowie is native to WA and keeps waterways clean by eating up waste scraps, bait and berley. Blowie and Djenark are similar; most humans don’t like them, but they end up cleaning up after humans anyways!

Blowies belongs to the family Tetraodontidae, and they typically have torpedo-shaped bodies, soft skin instead of scales, and fused teeth that form a beak. These fish also have the toxin, tetrodototoxin present in their skin, flesh, and internal organs. These toxins can kill animals, including humans, that eat them. Blowfish get their name because they are able to inflate their abdomens with water. This is a defence mechanism that makes the fish look bigger to predators. Blowfish also inflate their abdomens with air on removal from the water, and usually have trouble deflating. Therefore, it is best to get them back into the water as soon as possible.

It’s interesting to consider these dead Blowies as waste. What made the Blowies die? Old age, a predator, an injury, or a poison? Algal blooms naturally occur in Derbarl Yerrigan and will kill fish, but excessive nutrients and certain environmental conditions can cause larger growth. What if the poison can be traced back to a waste made by humans? Pesticides, that we use on plants and runs off into Derbarl Yerrigan is an example of an excessive nutrient.

Critical Discard Studies helps us raise important questions about and notice where waste goes, how it acts, what bodies it enters, and how long it takes for certain materials to ‘go away’. What might we find out by following fertilizer? What might we find out by following the carcass of Blowie?

The next time we encounter these dead Blowies, we should return them to the water, rather than leaving them for dogs to eat. But, where do they ‘go’? What does it mean to put Blowie back into Derbarl Yerrigan? We wonder if any species eats Blowie? What happens to the toxins and toxics when the carcasses of these Blowies decompose? Will they simply ‘disappear’? We learn that toxins are a natural part of this fish, unlike human-made pesticides that are toxic (Liboiron, Tironi, Calvillo, 2018). But does the difference really matter?

Leaving Derbarl Yerrigan we noticed a person, dressed in safety gear, spraying a pesticide on the grass.

New forms of response-ability

It would be too easy and too simple simple to try and tell the story of pesticide spray + rain + runoff = dead Blowie. That leads to a moralistic story that all too quickly turns into individual quick fixes that are grounded in attempts to “…delimit the world into one that is separable, disentangled, and homogeneous” (Shotwell, 2016; p.15).

Instead we are interested in how Derbarl Yerrigan activates new forms of response-ability. Children and educators notice the white foamy stuff, sometimes naming the water ‘dirty’. They notice how it can be ‘full of rubbish’ and are repulsed by the smell of rotting fish mixed with algae, salt, sand, and heat. These ‘dirty’ moments can be challenged. We can learn from Djenark, who is not repelled by the colour of the water, the brown-ish foam, or the plastic bag floating in the water. Paying attention to the different smells of Derbarl Yerrigan, that exist outside of ‘yuck’ or ‘gross’ is a start. Instead of generalizing and noticing all the ‘rubbish’ or reacting to smells by shouting, “Ewww, that fish stinks!” why not say, “I see a plastic baggy. Let’s pick it up and take it with us” or, “Oh, that’s a salty hot smell.” These are examples of how we might craft ethical responses to the impossibly complex worlds we are sharing with Derbarl Yerrigan, Djenark, and Blowie.

References

Liboiron, M., & Tironi, M., & Calvillo, N. (2018). Toxic politics: Acting in a permanently polluted world. Social Studies of Science 48 (3) 331-349.

Shotwell, A. (2016). Against purity: Living ethically in compromised times. Minneapolis, MN: Minnesota University Press.