We would like to acknowledge that this walk takes place on and with Noongar Country, in what is also now known as Perth, Western Australia, and with Derbarl Yerrigan, in what is also now known as the Swan River.

“Look, Derbarl Yerrigan is out!”

Yes, Derbarl Yerrigan is “out”; low tide, calm waters, and clear skies.

Muddy, sticky, and careful walking are happening along the shoreline.

Slowly, quietly, and with intention, Melanie walks across the beach.

Suddenly she stops and does not move. She is looking out across the sand. What is she looking at?

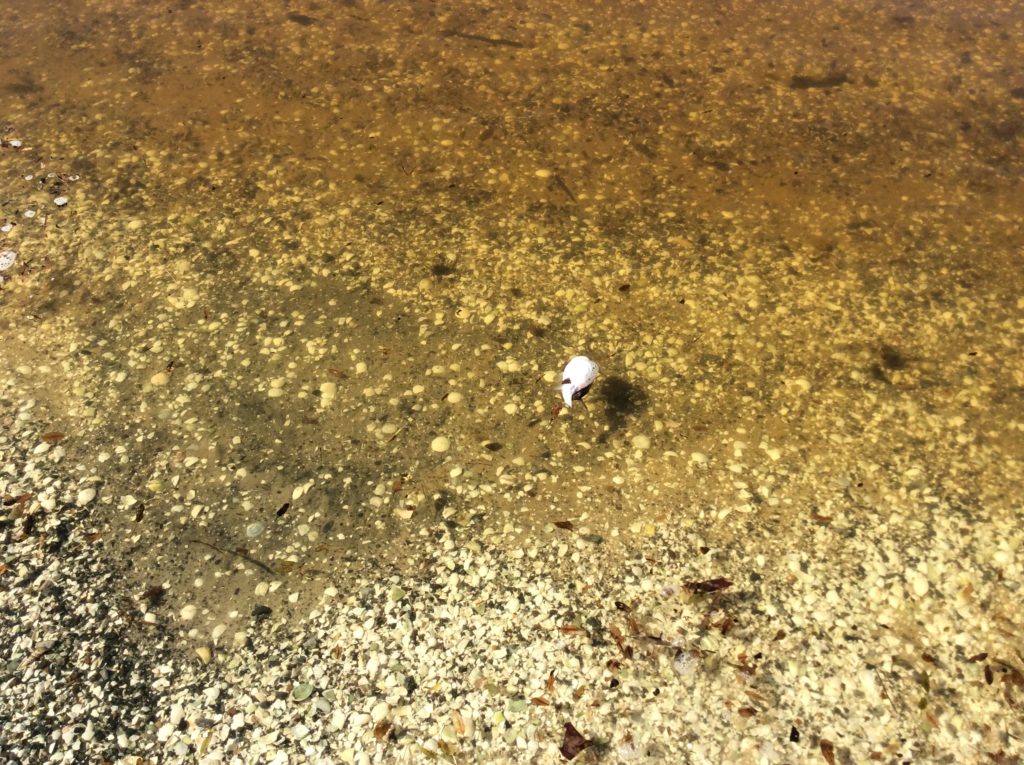

Following her line of sight, something glimmers on the beach, but it is unclear what it is.

Then, quickly another faint shimmer.

Not moving, Melanie points……at something…..but what?

Seagrass? Shells? Rubbish?

She lifts one foot up and slowly stretches it across the sand.

As soon as she places her toe onto land, she pulls it up.

What is it? What is going on?

Then, they become noticeable…….…..hundreds of Moon Jellies (Aurelia aurita), of all different sizes, are covering the beach.

We’ve mentioned Moon Jellyfish before in Blog 002 and have encountered them on previous walks, but not like this. It’s a Moon Jelly outbreak!

As I walk towards Melanie she looks up and then points towards the sand, saying, “Jellyfish!” Then, pointing in another direction, “There’s another one!”…….”Oh my god, look at that jelly!”

She asks, while pointing again, “What is that one?” “Right there!” She doesn’t move……

“Cute jellies”

With concentration and effort, she slowly and carefully continues walking around Moon Jellies.

“Hey, somebody help me.”

Looking closely for Moon Jellies

Immersed in my own thoughts, and trying hard to avoid stepping on Moon Jellies, I hear Melanie’s voice again, coming from behind, “Hey, somebody help me.”

Turning around, I see that she is frozen, not moving. I encourage her to “be careful”, and to “step around” Moon Jellies, but she remains still, not budging. Taking her hand, we both slowly continue walking down the beach. I ask why she did not want to move, and am told “Stingers. Don’t get stung.”

Out of the corner of my eye, I notice small white, greyish, and black lumps scattered along the shoreline. With interest, I lead Melanie towards these, but she is not budging.

Finally it becomes clear that the small lumps are dead Blowies (Torquigener pleurogramma, common blowfish). Unlike our previous walk, when we noticed about five or maybe six dead Blowies, this week there are more. Every few steps we encounter another dead Blowie. One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten, eleven, twelve, thirteen, fourteen, fifteen, sixteen, seventeen, eighteen……

While sitting with one of the dead Blowies, I remind the girls that I read it was best to place the stranded Blowies back into Derbarl Yerrigan. This way, their poisonous carcasses do not tempt curious dogs.

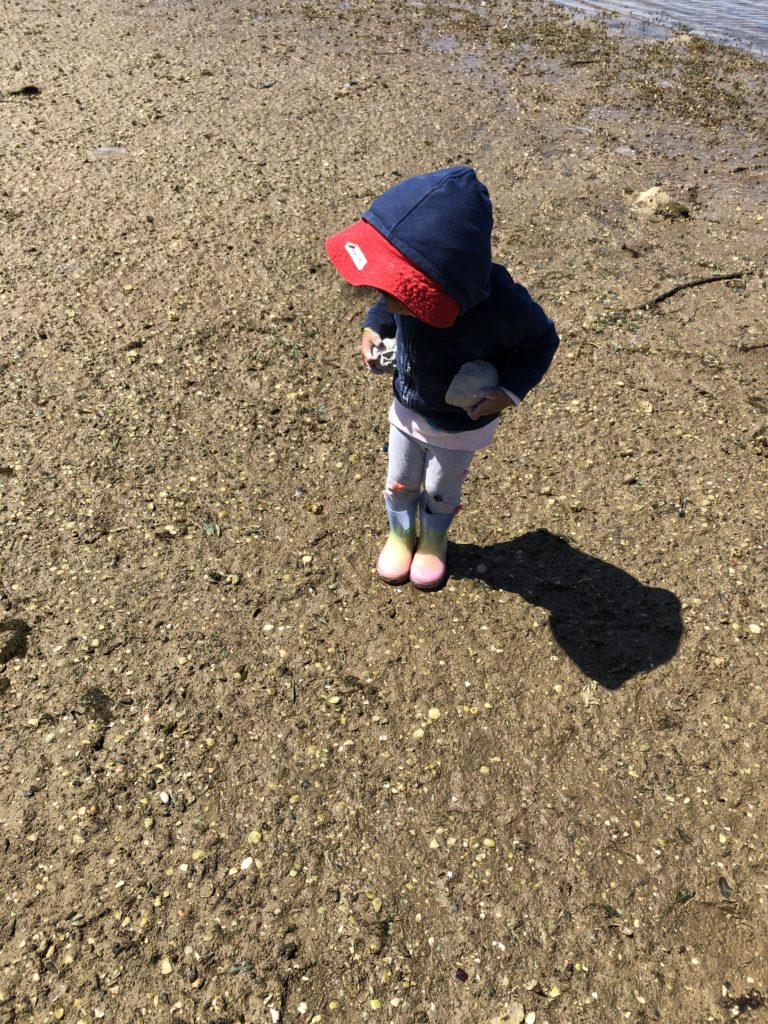

Then, with careful intention, the girls begin to thoughtfully picking up dead Blowies, and walk them out to Derbarl Yerrigan.

In silence and in awe, we watch the girls caring for the disregarded.

Caring for the disregarded and unloved 1

Caring for the disregarded and unloved 2

Caring for the disregarded and unloved 3

Caring for the disregarded and unloved 4

Caring for the disregarded and unloved with Djenark (Silvergull)